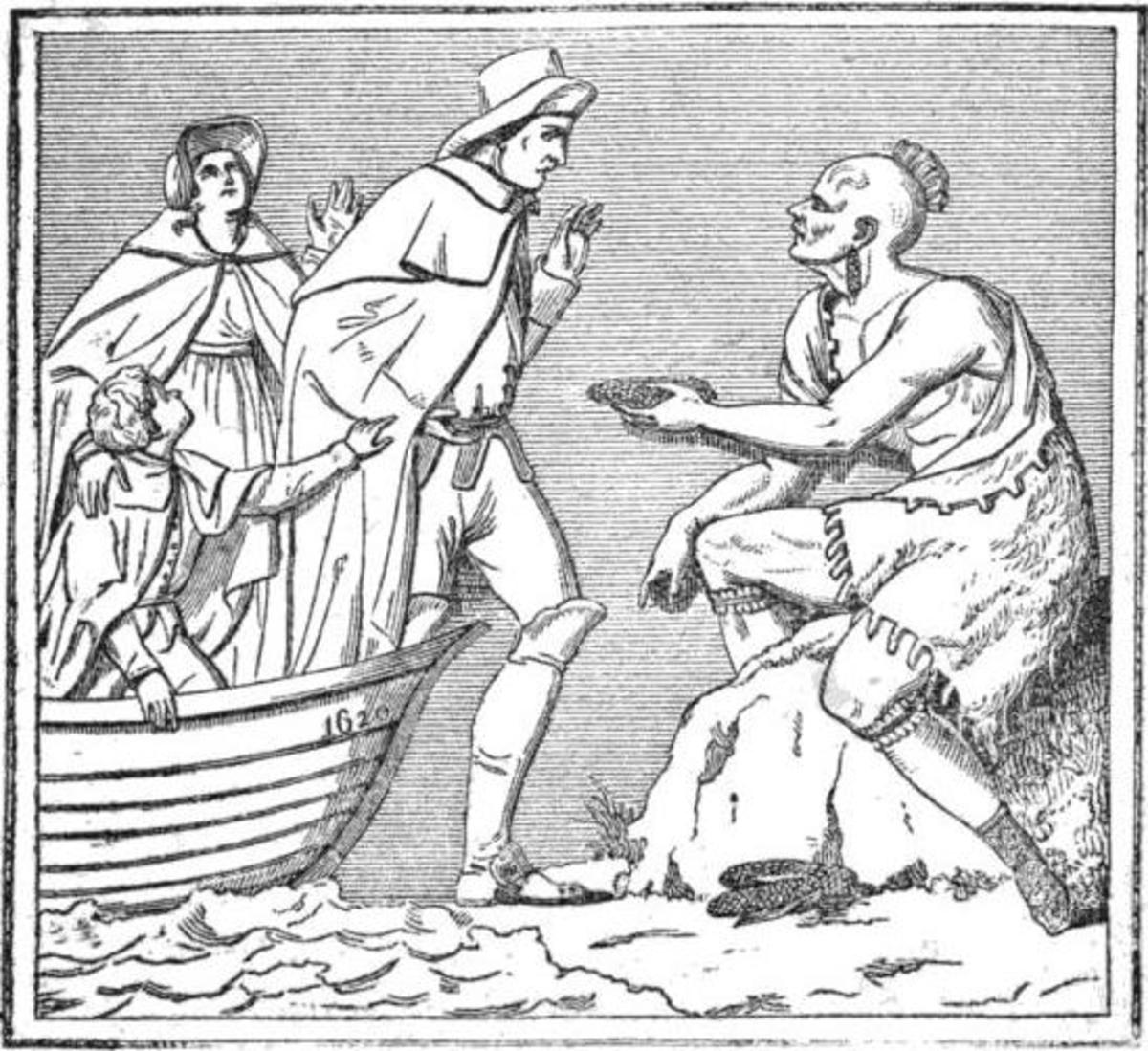

The story of the Pilgrim Fathers, who sailed across the

Atlantic in the Mayflower from Plymouth (England) to the New World in 1620, is

well known, but what is not so widely appreciated is that this was just the

start of a virtual torrent of emigration from England to the colonies during

the rest of the century.

Wave after wave of migrants left England for various

reasons. It has been estimated that as many as 400,000 people may have set

sail, with about half that number heading for North America and the rest going

further south. Given that the total population of England at that time was

about 5 million, that meant that getting on for 10% of the people of England simply

departed and never came back.

The first emigrants of the century – the Pilgrim Fathers –

were Puritans who were sickened by what they regarded as lax religious

standards on the part of the official Anglican clergy. They relied on God’s

advice to Abraham to “Get out of thy country … unto a land that I will show

thee”. They clearly believed that God was on their side when they arrived in

America and vast numbers of the native population caught and died from diseases

brought by the new arrivals and for which they had no immunity. God was

obviously clearing the way for his new chosen people.

The next big wave of emigrants was in the late 1640s. Many

of these had supported the cause of King Charles I against Parliament prior to

and during the English Civil War, which eventually swung in Parliament’s

favour. They could see no future for themselves under the regime that was

likely to follow Charles’s defeat and headed off for Virginia and other

American colonies. Given that the victors largely favoured the Puritan approach

to religion, the new emigrants were of a very different nature from the

previous batch.

The Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 caused problems

for other religious groups in England, most notably the Quakers, who were

appalled by the intolerance of the new regime towards non-conformist

denominations. Most prominent of these emigrants was William Penn, the founder

of Pennsylvania.

Not all the 17th century emigrants had political

or religious motives for setting sail. There were plenty of economic migrants

who left seeking to escape the poverty of their lives at home. Many had become

victims of changes to the economic structure of England that made life very

difficult for those at the bottom of the social pyramid. As woods and common

land was enclosed to become private property, prices rose and wages fell.

As might have been expected, there was adequate opportunity

for unscrupulous people to take advantage of the misery of others. Agents known

as “spirits” became active at fairs, markets and taverns where they would

entice people into emigrating with promises of vast riches to be made in the

colonies.

A huge number of emigrants were indentured servants who had

to work as virtual slaves for up to seven years before gaining their freedom,

in return for board and lodging. It has been estimated that only around 10% of

these people survived the experience.

Another source of emigration was the transportation of

prisoners from English jails – a practice that lasted well into the 18th

century until the American Revolution meant that Australia replaced North

America in this respect.

Genuine emigration – i.e. by those who wanted to emigrate as

opposed to doing so by force - waned towards the end of the 17th

century, largely due to the increased toleration provided by the so-called

“Glorious Revolution” of 1688.

A less acceptable reason was that the burgeoning slave

trade, which shipped vast numbers of slaves to the colonies from Africa, meant

that there was less need to import indentured servants from England, who were

in any case less suited to the harsh conditions of the plantations in the southern

colonies.

English migration may have declined at this time, but it was

soon replaced by fresh sources of travellers from countries that included

Ireland, Germany and Italy. However, the earlier dominance of English emigrants

left several permanent marks on the population of what would eventually become

the United States of America, most notably the universality of the English

language.

© John Welford