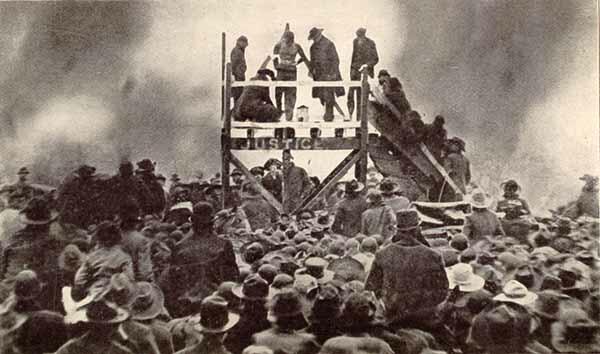

One of the ugliest aspects of an ugly time in American

history was the upsurge in violence by whites against blacks in the Southern

States during the late and 19th and early 20th centuries. A

particularly unpleasant custom was lynching – a black victim would be accused

of an offence, dragged from their home by group of white men, tried by a

kangaroo court and executed in public, usually by hanging. Records show that

more than 2,800 deaths could be attributed to the activities of lynch mobs

between 1880 and 1930.

The custom of mob violence leading to summary execution has

by no means been limited to the Deep South or the era of “white supremacy”, and

the terms lynch mob and lynching can be applied far more widely than to that

context. But where does the word “lynch” come from?

There seems no doubt that it derives from a person’s name

but which Lynch can take the credit, if that is the right word to use? On the

one hand is Charles Lynch, a Virginia planter (born in 1736, died in 1796) who

was a revolutionary during the War of Independence who punished suspected

loyalists in his own irregular court, thus dispensing “Lynch law”.

However, there was an unrelated Lynch, Captain William Lynch

(1742-1820), who claimed that he was the originator of the term.

William Lynch came from Pittsylvania County, Virginia. In

1780 he made a formal agreement with a group of his neighbours to deal with

local troublemakers by taking the law into their own hands and inflicting

whatever punishment they saw fit on any miscreants that they captured, although

they did not go as far as actually executing anyone – a severe thrashing was as

far as they went in terms of chastisement.

It does seem strange that two Virginians named Lynch, who

were probably unknown to each other, were doing something similar at roughly

the same time that could easily have led to a new word entering the language.

It sounds like a remarkable coincidence, but could this be an example of a

double attribution – Lynch law and Lynch mob deriving from different Lynches?

Whatever one might think of the rightness or otherwise of

their actions, they cannot be blamed for the utterly despicable deeds carried

out more than a century later to which their name was attached.

© John Welford

No comments:

Post a Comment