Zimbabwe gained her independence from British rule after a

long struggle that began with the “Unilateral Declaration of Independence” by

the white Prime Minister Ian Smith in 1965 and ended in 1980 after the Bush War

that brought Robert Mugabe to power. However, this was not the first war of

independence but the second.

The land that is now Zimbabwe came under British rule thanks

to the imperialist ambitions of Cecil John Rhodes, whose British South Africa

Company annexed vast areas of territory north of the Limpopo River. By 1895

Rhodes had acquired more than a million square kilometres between the Limpopo

and Lake Tanganyika, land that was given the name Rhodesia in May 1895. Today,

the northern part comprises Zambia and the southern part Zimbabwe.

However, the British advance into tribal lands was not

without opposition. The indigenous people, the Ndebele and the Shona, took up

arms to regain their lands and their cultural and political dignity. The

resistance offered in 1896-7 became known as the First Chimurenga by the

Africans but the Second Matabele War by the British. The name Chimurenga was

coined by Sororenzou Murenga, who had led his people during First Matabele War

in 1893. It can be roughly translated as “revolutionary struggle”.

Mlimo and Nehanda

The inspiration for revolt came from spiritual mediums such

as Mlimo, who persuaded the Ndebele that the white men were responsible for all

their woes, including introducing the cattle disease rinderpest (he may have

been correct in this) and bringing drought and plagues of locusts (for which

the whites were unlikely to have been guilty). However, the Ndebele had good

cause for revolt, in that the settlers had been responsible for thefts of land

and cattle and acts of rape and murder against the people.

Like most mediums of his kind, Mlimo was able to convince

the warriors that they were immune to the bullets of the white men, a claim

that has never been proved in reality. Also credited with inspiring the people

was a female warrior called Mbuya (Grandmother) Nehanda Nyakasikana, who was

largely responsible for getting the Ndebele and Shona to fight against a common

foe. The title of Mbuya was given much later in recognition of her role as the

grandmother of Zimbabwean independence.

The siege of Bulawayo

Mlimo had hoped to capture the town of Bulawayo, because

most of the British garrison was absent dealing with the “Jameson Raid”

emergency in the Transvaal, but attacks on settlers in the countryside started

before he could make his move, which he did in March 1896 by which time many

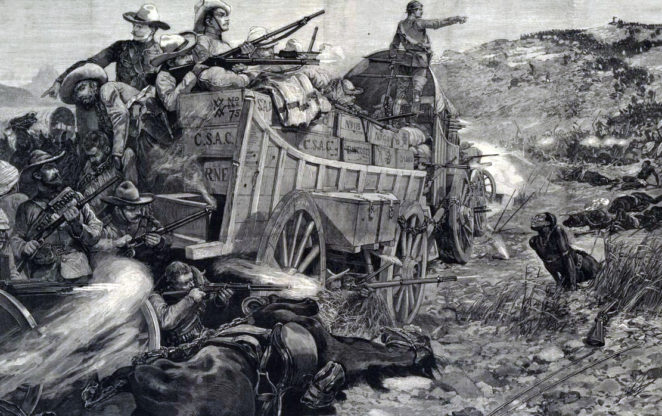

white people had escaped into the town for safety. There they built a “laager”,

a makeshift fortification along the lines of the Wild West “corral”, into which

they could gather at night for protection.

To say that Mlimo laid siege to Bulawayo would be something

of an exaggeration, because the Ndebele were fearful of the British maxim guns

that they had encountered during the 1893 war, and had no great desire to get

within range, despite any spiritual protection that their mediums might offer.

They even overlooked the need to cut the telegraph wires that connected

Bulawayo with the outside world, so the settlers were able to communicate and

call for assistance.

The settlers were able to send patrols out into the

countryside to rescue other settlers and to fight back against the Ndebele.

This became known as the Bulawayo Field Force, led by the remarkable American

adventurer Frederick Russell Burnham, who was to leave his mark on the world

for a different reason, mentioned below.

It was not until late May that two relief columns reached

Bulawayo, one from the north and the other from the south. These were able to

break the siege, and the settlers were saved. The second-in-command of the

restored garrison was Lt-Col Robert Baden-Powell, whose meeting with Frederick

Russell Burnham was to have consequences that spread far beyond Bulawayo.

The death of Mlimo

The British were now able to take the offensive against the

Ndebele, but they did so in more subtle ways than simply mounting full-scale

assaults, which were impossible when their enemy had the advantage of being

able to melt away into a countryside that was alien to the white invaders.

After the relief of Bulawayo, Mlimo and his warriors had retreated to the

Matobo Hills, an area of sacred significance about 20 miles to the south that

is dotted with many caves, in one of which Mlimo took refuge.

Burnham and an associate were able to infiltrate the area

and enter Mlimo’s cave without being seen, by using the skills of scouting such

as tracking and camouflage. There they waited for Mlimo to enter and shot him

dead when he appeared. They were able to escape back to Bulawayo despite being

chased by a hundred angry warriors. With Mlimo dead, the Ndebele resistance was

broken, and Cecil Rhodes was able to accept their surrender in person in

October 1896, offering them a land settlement in return for peace.

The war in Mashonaland

However, the war in Mashonaland, to the north and east of

Matabeleland, continued. The Shona were particularly cunning and calculating in

the planning of their rebellion. The official British report of the war stated:

“So cleverly was their secret kept, and so well laid the plans of the

witchdoctors, that when the time came the rising was almost simultaneous, and

in five days over five hundred white men, women and children were massacred in

the outlying districts of Mashonaland.”

In June 1896, the Shona launched an attack on the Alice

goldmine at Mazowe, and a number of settler families were murdered as they

tried to flee the area. The Native Commissioner, a man named Pollard, was

captured and killed by being beheaded.

It took many months for the rebellion to be brought under

control, and for the Shona leaders to be captured. Nehanda was eventually

caught in December 1897 and was tried for the murder of Commissioner Pollard.

She refused to convert to Christianity, as some other leaders did, and was

hanged. Her last words were “My bones shall rise again”, and many Zimbabweans

believe that it was her spirit that led to the successful Second Chimurenga

that created the modern country.

Apart from the legacy of the spirit of rebellion, the First

Chimurenga had another consequence that was much less to be expected. The

friendship that developed between Frederick Russell Burnham and Robert

Baden-Powell at Bulawayo led to Burnham passing on his scouting skills, which

Baden-Powell was later to apply to great effect during the Boer War and to

develop as a movement that has prospered and spread around the world, namely

the Boy Scouts (now known simply as The Scouts).

(See also: The Second Chimurenga: Zimbabwe's Successful War of Independence)

(See also: The Second Chimurenga: Zimbabwe's Successful War of Independence)

© John Welford

No comments:

Post a Comment